الموسيقى

MUSIC

Introduction

Music was a powerful tool for early Arab American immigrants, growing in popularity and prestige throughout the 1920s-1950s. It created and maintained a sense of community and collective identity for Arab immigrants in early twentieth century America. Mahjari musicians, often referred to as “old timers,” and their audiences acted as an extended multicultural family. Performers shared homeland musical and cultural traditions, reaffirming them for younger generations, even as they experimented with new musical language, instruments, and forms.

Tony Abdel Ahad and band. Courtesy of Anne K. Rasmussen.

Professionally oriented musicians gave life to weddings, picnics, rites of passage, and most family gatherings. Churches, community leaders, and social clubs, sources of patronage for Arab musicians, sponsored haflat, large music parties, and the mahrajan, a weekend communal festival, to gather the community for charitable causes and social events. Musicians, like Joe Budway, Russell Bunai, Tony Abdel Ahad, and Hanan Harouni traveled up and down the East Coast and beyond on the hafla circuit to perform Arab music and song at community engagements. Arabic music became widely accessible through vinyl records, both produced in new Arab American recording houses in the U.S. and imported from the Middle East.

Records of four Arab owned labels: Cleopatra, Arabphon, Maloof, and Macksoud. Courtesy of the Richard M. Breaux Collection.

Record Labels

Before Arab American record labels were established, many mahjari musicians signed with major American labels. Companies like Columbia and Victor signed Arab American musicians both for their “exotic” sound, as well as their potential marketability within and beyond the growing Arab American community. In the 1920s, musicians like Alexander Maloof, and later Abraham Macksoud, created their own 78 RPM labels to promote Arab music. By taking production into their own hands, producers created opportunities for less prominent musicians to enter the industry and for established musicians to experiment with, and innovate beyond, traditional styles. Some popular labels included Alamphon, Cleopatra, Abdel Ahad, Orient (El-Chark), Arabphon, and Maloof.

Because Arab American music lacked formal institutional support in the U.S., a reflection of the exoticization it suffered under mainstream record label managers and audiences, early recordings reflect the unique circumstances that led to modern, hybridized Arab American styles. Limited to the size of the record, classically long Arabic songs were condensed into popular, 3-4 minute tunes. Small studios led to smaller groups, 3-6 musicians (takht), as opposed to large ensembles. Musicians sought single-take recordings due to limited resources, which explains the spontaneity and imperfections that filled early recordings.

Alexander Maloof's Hybrid Music

Syrian American musician Alexander Maloof aligned much of his music with popular early twentieth century trends in Orientalist imagery and dance styles, including Harem Dances (Najla), Call of the Sphinx, and Tango Egyptienne.

In 1912, Maloof responded to President Taft’s call for a new national anthem with the song “America Ya Hilwa.” Subtly, Maloof incorporated hints of Middle Eastern sound in the song using notes to simulate the sound of an oud. His song was never adopted as the U.S. National Anthem, but New York public schools officially embraced it as a patriotic song for assemblies.

While popular among Euro-American crowds, the next wave of Syrian American musicians, led by artists such as Bunai and Abdel Ahad, rejected Maloof’s Arab-Western music for catering too much to American audiences.

Sheet music of “For Thee America,” by Alexander Maloof, published in The Junior Assembly Song Book, a collection of patriotic songs used by the New York City school system, 1912. Courtesy of the Arab American National Museum.

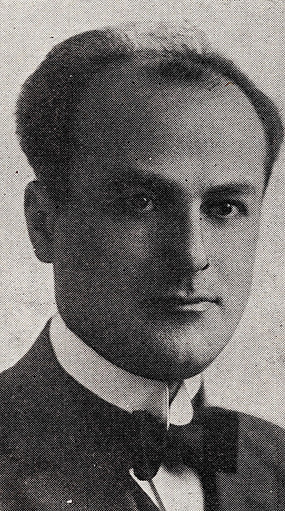

Alexander Maloof

Hymns recorded by religious leaders such as Rev. Agapios Golam and Germanos Shihadi were purchased by individuals throughout the diaspora as a means of preserving religious traditions. Courtesy of Richard M. Breaux Collection.

Religious Music

The recording and accessibility of religious music helped preserve Middle Eastern religious traditions both in the home and at spiritual gatherings. Early immigrants from the Middle East, especially outside of urban hubs, were often isolated from their religious traditions, or at best, members of small congregations where religion was practiced informally or intermittently as itinerant religious leaders visited communities. To keep musical traditions alive, some religious leaders recorded hymns for dispersal among the community. Reverend Agapios Golam of the Antiochian Orthodox Church recorded several Byzantine Chants on 78 RPM records with Consolidated Recording Corporation in New York City, which allowed individuals to record customized records. One thousand miles away in La Crosse, Wisconsin, Siad Addis, a Syrian immigrant and cantor at St. Elias Antiochian Church, acquired Golam’s records to practice for services. Other 78 RPM records with hymns recorded by early Arab American religious leaders have survived in private collections including some by Rev. George Aziz of the Maronite Church and Rev. Anton Aneed of the Melkite Church.

Religious Music

Later Musicians

Musicians who emigrated to the U.S. after the first wave of Levantine immigrants benefited from the hard work of their predecessors. Arab American recording companies were well-established, hafla and mahrajan touring circuits were wildly popular, and the hybridization and experimentation that resulted in a new, “modern” sound was generally accepted by Arab American audiences.

Arab American musicians, composers, and singers who came to prominence in the 1930s and 1940s had either been born in the U.S. or emigrated after cementing careers in the entertainment industry in the Middle East. Musicians from different ethnic backgrounds toured together on the hafla and mahrajan circuits across the United States in large groups and recorded songs on self-titled record labels. Ensembles started to incorporate American styles, which included adding instruments like saxophones and electric keyboards popularized by African American jazz artists.

Beginning in the 1950s, and gaining popularity in subsequent years, musicians further modernized and Americanized their sound with the advent of the Middle Eastern nightclub. Though Arab American musicians profited and gained prominence from the widespread appeal of these venues, both within their communities and in mainstream culture, they often Orientalized and exoticized their bodies, performances, and musical sound. Non-Arab audiences held stereotypical notions of the Middle East that further “othered” it as a static, homogenous region, which caused musicians to return to more traditional sounds.

Hafla advertisement from Brooklyn’s Syrian and Lebanese community newspaper, The Caravan, April 24, 1928.

Musical Innovations and Style

To create the heterophonic Arab sound, each musician played the same line on their instrument in different tones and speeds to create a layered sound. Their songs contained rhythmic patterns (iqa’at) and melodic modes (maqamat) aimed to stimulate the senses and immerse listeners into the music, bringing them to a state of intoxication (tarab).

Biographies

Alexander Maloof

Alexander Maloof (اسكندر المعلوف January 23, 1884 – February 29, 1956) was born in Zahlé and emigrated to Brooklyn, New York with his family around 1894. Maloof became an established pianist, composer, conductor, arranger, publisher, music teacher, and founder of Maloof Music Company. Maloof and his Maloof Oriental Orchestra wrote music for silent films, talkies, ballets, and Broadway plays. He is best known for blending Middle Eastern flair with Western style compositions that appealed to a hybrid audience.

Russell Bunai

Russell Bunai (رسل بني September 15, 1903 - October 26, 1996) was a vocalist, oud, and raqq player. A formative member of the “old timers,” or second wave of Arab American musicians, Bunai revived traditional styles of Arabic music that predated the nightclub era. He favored classical Turkish and Egyptian music to Levantine styles and preferred serious tarab music to folk music. In 1947, he founded Star of the East Records and became a leader of Arab musical tours, traveling the country to perform at cultural events with various artists including Joe Budway and Philip Solomon, who were collectively called al fursan thalathah (The Three Musketeers). (Photo courtesy of Anne Rasmussen.)

Hanan (Hanaan) Harouni

Jeanette Hayek Harouni (حنان هاروني November 8, 1929 – October 8, 2011), known by her stage name Hanan, was a classically trained Arab singer and actress. Born in Beirut, Lebanon, Hanan traveled across halfa circuits in Brazil, Argentina, and the United States. Performing in French, Spanish, and Arabic, Hanan’s global popularity soared between the 1950s through the 1980s. Hanan appeared on many labels, including Cleopatra Records and the short-lived, self-titled Hananphone label.

Muhammad Al-Bakkar

Muhammad Al-Bakkar (محمد البكار September 12, 1913 – September 8, 1959) was one of the most popular Arabic-language musicians and actors of the twentieth century. Early on, al-Bakkar established himself as a musician and actor in Lebanon and Egypt. He emigrated to Brooklyn, New York circa 1953 where his fame continued to grow throughout hafla circuits and in Fanny, a Broadway musical. Al-Bakkar performed throughout the 1950s until his untimely death in 1959.

Naim Karakand

Naim Karakand (نعيم كركند May 23, 1891 – 1973), born in Aleppo, was an integral member of the Syrian American music scene. As a violinist who tested the limits of adapting his European instrument to recreate Middle Eastern sounds, he began recording prolifically with ensemble groups in the 1910s. In the 1930s, he contributed to musical scores for films depicting Orientalist themes such as The Barbarian, Morocco, and Renegades. After a residency in Brazil, he returned to the U.S. where he continued to perform, record, and experiment with new Arabic jazz fusions in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sana and Amer Khaddaj

Sana Khaddaj (1919 - 1992) and Amer Khaddaj (1921 - 1979) emigrated from Palestine to Brooklyn in 1947, and later settled in Detroit. They became the most sought after Arabic musical pair in the Syrian American community performing across the U.S. and Canada at church events and social club gatherings throughout the 1950s and 60s. In 1966, Sana retired to care for the couple’s children while Amer continued performing and recording with other Arabic singers. In 1979, Amer was tragically killed during a robbery at their family store.

Kahraman (Olga Agby)

Olga Agby (كهرمان December 21, 1926 – May 8, 1992) was a singer and actress whose professional success spanned the Middle East and the U.S. After establishing herself as an artist in the Middle East, Olga emigrated to Brooklyn, New York circa 1948. Kahraman, Olga’s stage name, developed a successful career through the popular Arab American hafla and mahrajan circuit. Kahraman sang with other prominent Arab American musicians and recorded on Arabic-language labels like al-Kawakeb and Sun Records.

Tony Abdel Ahad

Anton “Tony” Abdel Ahad (أنطون عبد الأحد July 25, 1915 – December 25, 1995) was a prominent oud player in the hafla and mahrajan circuit during the second half of the twentieth century. Abdel Ahad, born to Syrian parents in Boston, Massachusetts, was influenced by traditional Syrian music and quickly developed his own, modern style. In 1947, Abdel Ahad created his own record company, Abdel Ahad Records, which lasted until 1949. (Photo courtesy of Anne Rasmussen.)

Hafla and Mahrajan

Hafla and Mahrajan Circuit Advertisements

Click on ads to learn more. Click the heart to "Like" images.

EXPLORE EARLY

ARAB AMERICAN MUSIC

_edited.png)